In practical science and technology – the stuff that has real applications in the world – decisions often need to be made with very little knowledge. In engineering ethics are at the core of practice – the professional obligation is to do everything possible not to put the public at increased risk. Bridges and dams have very little risk. Aircraft have obvious risks that we accept on the basis of benefits. It is ultimately all about risk and benefit – the risks the public are willing to take to get the benefits of a technology.

Powerful and novel technologies – and gene technology easily qualifies – require a broad assessment of risks and benefits – as well as extreme caution in giving weight to unknown unknowns. There are three broad approaches.

1. Utilitarian – the assessment of risks and benefit by government.

2. Natural rights – the mooted right of an individual not to have risks imposed.

3. Contract – risks and benefits are assessed by those exposed to risk and imposed by social contract.

The first involves a level of trust that doesn’t exist and – I argue – should not. Government bodies have political masters and scientific committees are self-selected. One should not underestimate the potential for bias. Science itself is more often wrong than not. Eighty percent of uncontrolled scientific studies are wrong, biased or data is manipulated to make results seem more interesting. Interesting results get published and truly interesting results are exceedingly rare. Science commonly comes to conflicting conclusions. Science is certainly not value free. In the public sphere science is always grossly over simplified and usually enlisted to support a point of view. The second means of addressing technological risks and benefits is ultimately unworkable if sectional interests have a veto of any particular technology. The most common fallback position is the third. Risk here is entirely individual and subjective.

The genetically modified crops that are most widely implemented are those engineered to produce a toxic protein to reduce insect attack – and those engineered to be resistant to glyphosate weedicide. The toxic protein is produced by genes taken from a soil bacterium – Bacillus thuringiensis – and inserted in corn, cotton, soybean, canola, eggplant, potato, etc. Bacillus thuringiensis has in fact been used in organic farming for many decades with little apparent ill effect. Herbicide resistant plants have soil bacterium genes inserted to produce an enzyme that interferes with the action of glyphosate. BT plants leave a legacy of toxic proteins in the food supply and soils. In organic farming Bacillus thuringiensis is applied in a foliar spray and degrades within a few days in the environment. Weedicide resistant plants require use of glyphosate – a weedicide that causes cancer in people and washes into soils and the environment.

The BT-toxin enters the bloodstream – and crosses the placental barrier – in people. It kills red blood cells in the bone marrow of mice. It causes observable changes in the livers and kidneys of rats. The risks may be minor – but it adds to the mountain of physiological stressors we face every day. The acceptance of even small risk demands real benefit to individuals. On a metaphysical level GMO’s bypass sexual reproduction – and where’s the fun in that – to swap genes across the species barrier. It is something to be exceedingly cautious about.

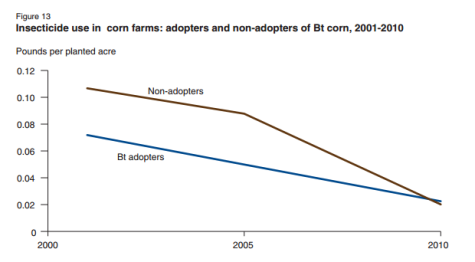

GM crops are now grown on 50% of US farmland. A report from the US Department of Agriculture this year compared GM with non-GMO crops since 1995. There were no discernible differences in crop yields or in returns to farmers. Nor are there obvious price discounts for consumers. Indeed – with the industry heavily lobbying against food labelling – it may be more difficult to tell the difference at the point of sale. The lack of integrated pest or weed management – the dependence on one internally produced toxin and one weedicide – at the farm level has led to increasing pest resistance to the BT-toxin and weed resistance to glyphosate. Pesticide use on GMO and non-GMO crops is now the same – the reduction in both is the result of ‘precision agriculture’ – and glyphosate use is soaring. It may well be that the benefits in this are all accruing to Monsanto and that the externalities of environmental, health and soil impacts are not internalised. Time to impose an environmental levy?

Source: USDA

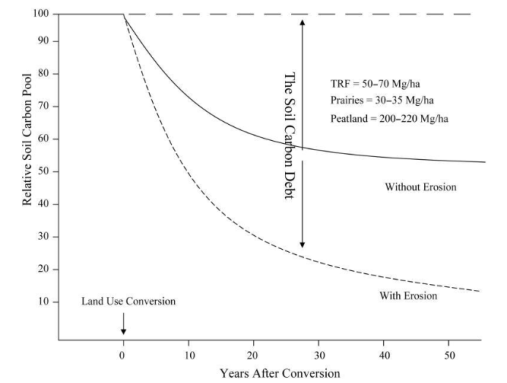

Neither of these genetic approaches to agriculture seems calculated to add to soil health. The health of soils is the underlying key to high productivity and healthy plants and food. Dr. Elaine Ingham explains healthy soils in the video embedded below. The idea is to reduce inputs of poisons and fertilisers that destroy the symbiotic soil and plant ecology. Get interested in this. This is the way to grow healthy, disease and pest resistant and nutritious plants, sustain environments, drought proof agriculture and reverse the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. It creates an obvious imperative.

“The urgent restoration of degraded forests and landscapes in drylands is essential if the global community is to meet the challenges posed by desertification, food insecurity, climate change and biodiversity loss, among other negative trends.” FAO

Here’s a perspective from farmers – on building living soils – that is well worth looking at. The green revolution accelerated the destruction of soil health across the planet. There is a price to be paid.

Source: Lal and Follett, (2008)

For large scale weed and pest management the future seems more likely robots than more of the same.

Source: Queensland University of Technology

The green revolution increased productivity by adding inputs of fertilisers and toxins. It worked of course – it was a temporary solution to the problem of soil exhaustion – but at a high cost in further soil and environmental degradation. We are losing aquatic species and dead zones off the coasts of developed nations are growing because of excessive nitrogen inputs. Poisons accumulate in our environment. The green revolution has hit a production limit that will only get worse as the final remnant of soil health on agricultural lands is exhausted. At the same time costs of fertilisers, insecticides and weedicides are increasing with oil costs. There is a crunch coming in conventional agriculture – and it has little to do with climate change.

To avoid peak food – and peak biodiversity – we need another way and it doesn’t seem to be the Monsanto way. Instead there is great hope that we can – from the bottom up – restore agricultural lands and ecosystems to balance the human ecology. Living soil holds more water to be more drought resilient, contains more carbon, increases productivity, promotes healthy plants that require fewer chemicals and enhances global environments.